“Use new technology, but be careful.”

Thus is the caution of John Sofos, Colorado State University professor and director, Center for Meat Safety & Quality. “Food is a very complex, non-homogenous system consisting of different components,” Sofos said. In addition, the environment in which it is produced is diverse, non-predictable, and non-homogenous—and it is these factors that make contamination testing difficult.

There are many test methods, including a number of rapid methods that are effective, but, Sofos said, “How do we get it to find that cell that is of concern to us in a non-homogenous food? How many samples do we need to take? How do we need to take them?”

It isn’t an issue of whether the test can detect the pathogen, rather, he said, it’s whether there is enough in the sample being tested at the time the sample is pulled to be detected. “I don’t doubt the methods work in seconds—provided there is enough there,” he said. If the contaminant for which the test is being conducted is present, in a sufficient amount, it can be detected in seconds or minutes, but it has to be found first, he explained. For this reason, it is often necessary to grow the microorganism to a level that can be detected.

It isn’t an issue of whether the test can detect the pathogen, rather, he said, it’s whether there is enough in the sample being tested at the time the sample is pulled to be detected. “I don’t doubt the methods work in seconds—provided there is enough there,” he said. If the contaminant for which the test is being conducted is present, in a sufficient amount, it can be detected in seconds or minutes, but it has to be found first, he explained. For this reason, it is often necessary to grow the microorganism to a level that can be detected.

Thus, the real challenge, Sofos said, is applying the methods in the field, particularly in non-homogenous foods, such as ground meat. It is not feasible to test all the food, but because the contaminant may be in any one part of the food and not another, anything less than sampling everything could miss a contaminant. So, he said, “How do we get these methods to work as quickly as they can work and as effectively as they can work?”

Which takes us back to the initial caution … Use new technology, but be careful. “The answer,” Sofos said, “is that there are many ways, many places, many uses of testing of food. But don’t rely on testing only to tell you whether the food is safe or unsafe.” Rather, apply proper processing and management practices, including preventive controls and HACCP to validate and verify your controls, or, in other words, to test your controls in addition to testing your food.

New Innovation in Testing.

Agreeing that the greatest challenge in testing is the food matrix itself, Julia Bradsher, CEO of the non-profit Global Food Protection Institute (GFPI), sees the ultimate goal of rapid testing to be the ability to do so without pre-enrichment in the food matrix. To advance this, as well as the development of other food protection technology, GFPI’s Emerging Technology Accelerator (ETA) invests in innovative technologies that improve public health and economies that are impacted by contaminated and adulterated food.

Most recently, ETA invested in two start-up companies that have developed products that rapidly detect pathogens in food, and awarded funding to a third that is developing antimicrobial packaging. These companies are:

- nanoRETE — provides real-time detection of pathogens using customized nanoparticle biosensors. The platform has the ability to test for numerous pathogens and toxins using a handheld device which generates screening results in about one hour. The platform technologies were developed at Michigan State University initially in response to military requirements for food safety and security.

- Seattle Sensors — Seattle Sensors uses a portable surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technology to detect biohazards in food and the environment. The device, based on University of Washington research, will protect food sources by monitoring production and analyzing the environment for hazards. It can be customized to detect pathogens, allergens, and toxins.

- Micro Techno Solutions — In addition to the above, GFPI partnered with Great Lakes Entrepreneur’s Quest (GLEQ) to name Micro Techno Solutions the winner of a business plan competition for ventures in food safety. The company is developing an antimicrobial packaging material to prevent contamination of food during transportation.

Selected from 40 companies vetted during a year-and-a-half-long search, Seattle Sensors and nanoRETE were chosen based on criteria such as risk/rewards analyses and the potential to be commercially available within 36 months, Bradsher said. In addition, the technologies were required to be field based and, she added, “be a technology that doesn’t require highly trained professionals for the testing.”

GFPI, itself, was founded through start-up funding by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation for the purpose of driving the adoption of food protection policies and practices to improve public health and reduce mortality, morbidity, and economic costs associated with foodborne illnesses. “We continue to look for technology and make investments in [food protection] technology,” Bradsher said. “So if someone is looking for investors, they should contact us.”

The author is Editor of QA magazine. She can be reached at llupo@gie.net.

Explore the August 2012 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- Director General of IICA and Senior USDA Officials Meet to Advance Shared Agenda

- EFSA and FAO Sign Memorandum of Understanding

- Ben Miller Breaks Down Federal Cuts, State Bans and Traceability Delays

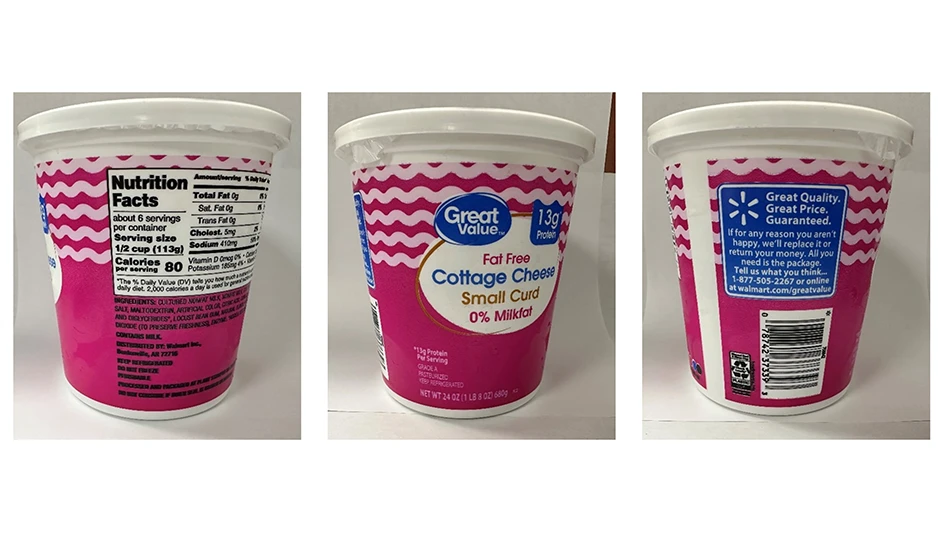

- Michigan Officials Warn Recalled ByHeart Infant Formula Remains on Store Shelves

- Puratos USA to Launch First Professional Chocolate Product with Cultured Cocoa

- National Restaurant Association Announces Federal Policy Priorities

- USDA Offloads Washington Buildings in Reorganization Effort

- IDFA Promotes Andrew Jerome to VP of Strategic Communications and Executive Director of Foundation