Jomanda Cruz

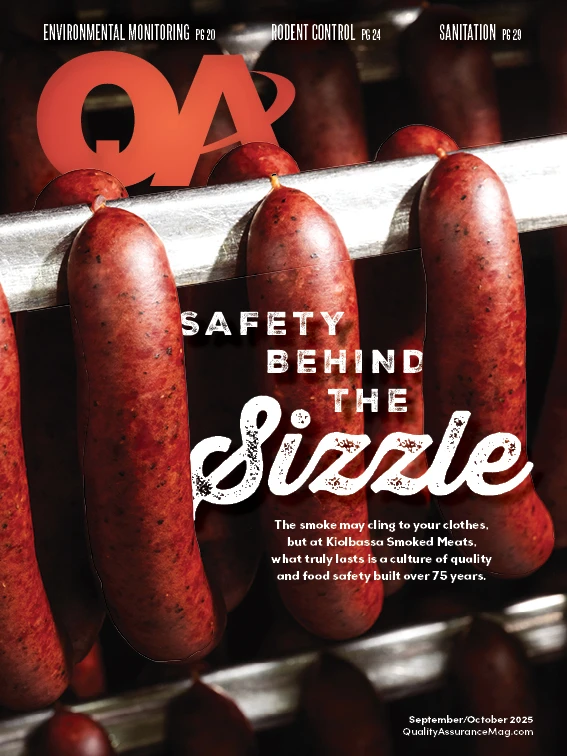

What lingers longest after a tour of Kiolbassa Smoked Meats isn’t the chill of the cooler or the clatter of machinery — it’s the smoke.

It seeps into your clothes, clings to your hair and follows you long after you’ve left the Kiolbassa facility on San Antonio’s West Side. Employees joke about it — how the aroma of hickory stays with them as they head to the grocery store or back home to their families.

“You’ll be smelling like it for days,” said Marcos Salinas, food safety and quality assurance manager at Kiolbassa.

The smoke isn’t just a smell. It’s the mark of work that blends craft and care with an unwavering emphasis on safety and quality.

At Kiolbassa, every batch of sausage is made with an old-school respect for tradition and a modern vigilance for food safety. The family-owned company, founded in 1949 by Rufus Kiolbassa, started with a modest smokehouse and a family name that sounded suspiciously like the Polish word for sausage. Today, the brand is linked to customers across the United States, Mexico and beyond, without sacrificing its roots.

DESTINED BY NAME.

Some customers assume “Kiolbassa” is a twist on “kielbasa,” the Polish word for sausage.

It’s not. It’s the family name — one that, some might say, was predetermined by fate.

“[Our CEO] Michael Kiolbassa always jokes, ‘With my last name Kiolbassa, I was destined to be a sausage maker,’” said Erin Covarrubia, Kiolbassa brand strategist.

That destiny reaches back generations. The Kiolbassa family immigrated from Poland’s Upper Silesia region in 1854, settling in Panna Maria, Texas, the first Polish settlement in the U.S.

“They came from Upper Silesia, driven by economic hardship, the promise of land and the desire for religious freedom,” said Michael Kiolbassa. “At the time, Poles were facing cultural suppression under Prussian rule, which sought to Germanize them. Their decision to settle in South Texas was also influenced by a Polish friar who was already serving in the region and had actively recruited settlers.”

In 1949, Michael’s grandfather, Rufus Kiolbassa, opened Kiolbassa Smoked Meats on Brazos Street. That location still exists today, with the addition of a larger facility a block away on South San Marcos.

“Every Kiolbassa since then has just been destined to run it,” said Covarrubia.

Rufus’s son, Robert, took over after his father’s passing in 1960, carrying the torch for decades. His son Michael followed in his footsteps, joining the company’s sales team in 1987.

Today, as CEO, Michael leads the third generation with a reverence for tradition and a bold transparency about food safety and quality. He often quotes his father: “People will remember the quality long after they forget the price.”

FROM SMALL SHOP TO SUPERSTORES.

For years, Kiolbassa has been a San Antonio staple.

“Anywhere I go in town and people ask, ‘Where do you work?’ I say Kiolbassa, and they just light up,” said Salinas. “They’re like, ‘You work at Kiolbassa? I buy that all the time!’ I’ll give packages to neighbors, my parents, my in-laws — they are constantly asking for it. I didn’t realize how much of a staple it is in San Antonio until I started working here. I realized this is more than just a name. It’s the product, it’s the culture, and then, of course, everything they do for the community.”

Kiolbassa has forged its reputation in the San Antonio community over the last 75 years. But in the 1980s and 1990s, Michael pushed the brand beyond its local roots. Distribution partnerships with Costco and Sam’s Club fueled growth, while traditional grocers like H-E-B and Publix cemented Kiolbassa’s reputation in the South. Today, the company sells about 20 million pounds of product annually, said Salinas, shipping across the U.S. and to Mexico. Most recently, the company has started supplying military commissaries overseas.

Scale hasn’t diluted craft. Kiolbassa still makes sausage the same way it did 75 years ago — in small batches, with precision and skilled specialists at the helm.

Many of those specialists have been with Kiolbassa for decades, passing down skills and standards from one generation of employees to the next. Take Kiolbassa’s kitchen lead, Mariano, who has been with the company 24 years.

“When you have someone like that in a room to lead everybody, it definitely helps out a lot,” said Salinas. “We need people like that to come around and visually be able to say, no, that’s not chopped right; no, these aren’t stuffed correctly; no, there’s too many links on this stick. He makes his rounds and lets people know what to do and when to do it. It helps. That’s one thing that we have here is longevity.”

In an industry where thousand-pound industrial runs are common, Kiolbassa still insists on 150-pound batches of meat — each hand-weighed, tracked and inspected.

“It’s the same way that Michael’s dad and Michael’s grandfather did it 75 years ago, where they’re hand weighing each spice bag and doing 150 blocks of meat,” said Salinas. “It makes sure that it’s a craft product; it’s authentic. We’re able to keep a better handle on the way we’re chopping and cooking everything.”

CULTURE YOU CAN TASTE.

Step inside the plant, and you’ll quickly learn Kiolbassa isn’t just about sausage. It’s about family — in name and in practice.

“I know a lot of places say we are like a family, but I can honestly say that that’s the actual feeling that I got here,” said Salinas, who joined the company a decade ago, expecting to stay for maybe a few years. Instead, he rose through the ranks to manage the FSQA department under the leadership of Tabatha Barnes, senior director of FSQA at Kiolbassa. She and Lance Peavler, vice president of QA and operations, helped build the company’s FSQA program into what it is today, with Peavler ensuring Kiolbassa became a federally inspected facility in 2004.

The work family isn’t just metaphorical. At Kiolbassa, it’s common for cousins and siblings to work alongside each other, and there are multiple mother-daughter and father-son duos on the team. In some cases, multiple generations clock in together.

That dynamic builds accountability.

“You don’t want to hear at the dinner table that, ‘Oh, we would have done better had you done better,’” Salinas said. “There’s a sense of pride that comes with it.”

Employees carry that pride home. On Fridays, team members can take home a package of product.

“There are people that have worked here 15 years that still take a package home every Friday,” Salinas said. “They wouldn’t do that if they didn’t enjoy our product.”

BOBBY’S LEGACY.

The sense of family extends beyond plant walls. Bobby’s Legacy, named for Michael’s father, has become a cornerstone of Kiolbassa’s community giving.

Through the program, groups that purchase sausage in bulk receive additional product at no cost. For every two boxes purchased, Kiolbassa donates one.

Schools, churches and Little Leagues — including Salinas’ son’s team — across San Antonio have benefited. Customers return to Kiolbassa’s store on Brazos year after year to stock up on food for fundraisers.

“We’ll get people that come in and say, ‘I go to this church. You guys have donated for the past 20 years. We’re here again for our fall festival.’ They come back over and over again,” said Covarrubia. “One program has touched so many lives, and I feel like it drives loyalty to our brand.”

For Kiolbassa, giving back is part of the culture — the same culture that underpins its approach to food safety.

QUALITY AS A PROMISE.

All of this — the heritage, the craft, the family and the giving — feeds into the one thing Kiolbassa refuses to compromise: quality.

Morning cuttings are a ritual, with leadership tasting and inspecting product from the previous day. If something is off, adjustments occur immediately. And if it’s right, Michael himself delivers the ultimate seal of approval, delivering his now-famous verdict after taking a bite: “That’s a damn good sausage.”

How the Sausage Gets Made

The steel door swings open, and the cold air bites, carrying with it the metallic tang of fresh meat. Inside, large containers of raw meat from suppliers line the receiving cooler, each tagged with barcodes for traceability.

“This is where we have all of our incoming raw materials, all of our meat,” explained Salinas on a tour of the facility.

Temperature is closely monitored, and Salinas’ FSQA team checks each lot for compliance before it enters production. Every shipment is logged, labeled and scanned.

“We use first in, first out,” Salinas said, pointing to the labels. “When those get taken to the kitchen, they get scanned, so we know based on a lot number what meat was used that day and what kind of materials we used.”

SPICE UP YOUR LIFE.

Leaving the cooler, the next step is the spice room, where the air instantly changes. Aromatic wafts of pepper, garlic and cumin mingle as workers measure out blends. Bags of spices are carefully weighed, sealed and labeled. Each bag is destined for one 150-pound batch of meat — no more, no less.

“All the spice bags are made by hand. Each one is custom,” Salinas said. “A label is put on so we know exactly what this product is for, when it was made, and then if we scan that barcode, we can tell everything that goes into it — the spices, the amounts, the use-bys, the lot numbers. In case there’s any kind of issue, we have that traceability on everything.”

There’s a rhythm to the work: scoop, weigh, seal, scan. Unlike larger plants that process thousands of pounds at a time with pre-mixed seasoning, Kiolbassa still does it by hand.

THE KITCHEN: PRODUCTION'S HEARTBEAT.

With spices bagged and tagged, the blends move forward into the kitchen, where calm gives way to clatter. Here, sound and motion take over as fresh meat meets its seasoning. Amid the steady thrum of grinders, the clank of steel and the low roar of machinery, workers in powder-blue frocks move with practiced efficiency, weighing meat, feeding it into choppers and adding ice and spices to create a soupy mix called a pre-blend.

“All of our products are very simple,” said Salinas. “It’s the meat and then it’s spices. There’s no fillers, nothing else that gives it an extra flavor, no liquid flavoring or anything like that. Everything is like you saw in the spice room — authentic, real spices.”

A worker hefts a 150-pound block of beef onto the scale, while another carefully watches for stray bone fragments. This is one of three checkpoints for bone inspection, said Salinas.

“As far as the specialty positions in our company, you have the chopper operator and the smokehouse operator,” he said. “[The chopper is] making sure that our product looks the same as it has for the past 75 years. It has a nice, coarse grind. If he chops it too much, it starts to look like hot dogs. If he doesn’t chop it enough, then you have issues in the stuffing. He has a very tight range that he has to maintain.”

Consistency is key. The day’s schedule lists 190 batches to be chopped. That’s nearly 30,000 pounds from this room alone, with every batch expected to look and taste the same.

LINKS TAKE SHAPE.

From the grinder, the meat mixture feeds into two stuffers: one automated and one manual.

“This [older] one’s a little more hands-on,” said Salinas. “You have to have a very skilled person here making sure that it’s stuffed tightly. This one’s more automated. It’s a lot faster. You can see how it’s just spitting them out, and they line them up on the sticks and hang them up.”

Natural hog casings fill to form sausage links that line up neatly on metal rods. Workers tie off the ends and hang trolleys with links to be delivered to the smoker.

“It provides that really good snap that you want when you’re barbecuing sausage — and here in Texas, that’s all year long,” said Salinas.

Each trolley gets tagged with the batch number, time and date — another layer of traceability.

UP IN SMOKE.

The trolleys roll forward into the smokehouse — the source of Kiolbassa’s signature flavor. A dense, savory haze of hickory smoke seeps into every link. Rows upon rows of sausage wait for their turn in the carefully controlled heat.

Twelve trolleys can fit into the smokehouse at a time. Temperatures are monitored closely, with operators checking times and internal readings to ensure every batch reaches the right point for both flavor and safety.

The smokehouse operator is one of the company’s most important positions, Salinas said.

“He has to maintain the temperature inside, and he has to know what the weather is outside, because if it gets too humid, that can affect the [sausage] color,” said Salinas. “If a cold front comes, they have to adjust the temperature. Color is a big deal. We want to get that nice, red sausage color that everybody’s familiar with. That’s where heat comes into play.”

Some people think of the smokehouse as a massive grill, where you just set it and walk away, but there’s much more to it than that, Salinas said.

“It’s not like that at all,” he said. “He has to monitor every few minutes, check the system, open the door and make sure everything is just like it should be.”

That attention to detail extends to the fuel itself. Unlike manufacturers that rely on artificial smoke flavoring, Kiolbassa insists on the real deal.

“A lot of other places use synthetic smoke or synthetic smoke flavoring,” Salinas said. “This is 100% wood. Most of ours is hickory. Some of the other ones, we might use a different blend.”

The chips feed into a hopper and burn down to ash, leaving behind the rich, smoky flavor that defines Kiolbassa sausage.

“To me,” Salinas said, “it’s that smoky flavor that you really want from a sausage.”

“Consistency is the key,” Salinas said. “I can come down at 7 o’ clock in the morning, and I can come down at 7 o’ clock at night, and it’s different people, but they’re doing the exact same task. They’re doing it the exact way they did it yesterday, and last year, and 20 years ago, and I think that’s what really helps our brand.”

THE BIG CHILL.

Suddenly, the air is biting cold again. Those trolleys of sausages, freshly smoked until piping hot, roll into their next destination: the chill room. Here, product temperatures drop to 40° F within hours, following USDA guidelines.

It’s a race against time: Cool too slowly, and you risk microbial growth; too quickly, and the links wrinkle.

“Typically, we can get them chilled down in about three to four hours,” Salinas said. “That’s why we’re able to make it in the morning, three hours to cook, three hours chill, and then, get ready to pack.”

PACK IT UP.

The last stop in the production line is the packing room, where workers inspect links as they move down the line, cutting, portioning and vacuum-sealing each package. One quality control inspector, easy to spot in her red hat, documents weights, labels and codes as product moves forward.

“They’re looking to make sure that everything looks good, that it feels OK, that it looks OK, the color, the length,” Salinas said. “Anything is off, we’ll put it into our reworks to be used when we work in the kitchen. Everything that comes out, we want it to look presentable and as good as it possibly can.”

Packages run through a metal detector, then labeling machines stamp them with lot numbers, dates and USDA marks of inspection. QA inspectors stand close by, clipboards in hand, documenting each step.

“From here, QA will do a final inspection, make sure that … the packages look good, make sure everything matches, there’s no incorrect information,” Salinas said.

The tour ends where it began: with a product simple in appearance but layered in oversight. From the cold blast of the receiving cooler to the smoky warmth of the smokehouse, every room tells a chapter in the story: craft married to quality and food safety.

Explore the September/October 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- New Strain, More Illnesses Reported in Moringa Leaf Powder Salmonella Outbreak

- Kiwa ASI Expands Canadian Presence with Addition of TSLC

- Samples Collected by FDA Test Positive for C. Botulinum in ByHeart Infant Formula Investigation

- FDA Releases Total Diet Study Interface

- Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association Offers Student Scholarships

- Mandy Sedlak of Ecolab on Building a Career in Food Safety and What’s Next for the Industry

- Kroger Shares 2026 Food Trend Predictions

- USDA Announces New World Screwworm Grand Challenge