Life aboard a nuclear-powered submarine during the Cold War wasn’t glamorous. It was routine. For some, it was claustrophobic, but for everyone, it was relentlessly disciplined.

From 1989 to 1992, I served aboard the USS William H. Bates (SSN-680), a fast-attack nuclear submarine. Our lives ran in loops: standing watch, equipment checks, emergency drills, training, sleep. And then repeat.

In the cracks between the chaos, there was food — not always comfort food, and rarely meals you’d brag about — but enough to keep us going.

In the early days of a patrol, we’d have fresh salads, real eggs, boxes of cereal with familiar mascots and even tubs of frozen ice cream, rationed like gold. But within a week or two, the fresh items ran out. Our meals turned into a rotation of frozen meats, dehydrated potatoes, canned vegetables and powdered soft-serve mix that never quite reconstituted the way you’d hope.

The galley always smelled like grease, metal and soap. But when the night cook baked bread from scratch, the scent drifted down the narrow corridors like a postcard from home. It reminded us, in that windowless world, that someone, somewhere, might be thinking of us.

That delicious bread — and everything else we ate — had to follow one absolute rule: It had to be safe.

AN UNDERWATER PRESSURE COOKER.

At hundreds of feet below the surface, there is no emergency room. There’s no backup crew. There’s no calling in sick. One contaminated meal could compromise the health and effectiveness of an entire submarine. Food safety wasn’t a guideline. It was a requirement for mission readiness.

The Navy’s Cold War submarines didn’t just advance stealth and surveillance — they helped pioneer new standards in food science that would ripple far beyond military use. Submarines faced a unique problem: long-term deployments with no resupply, minimal waste tolerance, zero room for error and no margin for medical failure. Every item loaded aboard had to be nutritionally sufficient, compact, shelf-stable and pathogen-free. These constraints drove innovation.

THE RISE OF FOOD IRRADIATION.

To reduce the risk of foodborne pathogens like E.coli, Clostridium botulinum, Salmonella and Listeria, the Navy, in partnership with the Department of Defense and the FDA, explored food irradiation — a method of using ionizing radiation to eliminate pathogens without cooking or chemically altering the food. This idea met public skepticism, but military research moved forward with urgency:

- 1953–1958: Early feasibility studies explored irradiating meat for long-term storage.

- 1960s: The Navy tested irradiated ham, bacon and beef for submarine and NASA missions.

- 1963: The FDA approved low-dose irradiation for certain foods — first for wheat and potatoes, then bacon — for military use.

- 1970s–1980s: Irradiated food was deployed in submarines and space missions, where sterile, shelf-stable products were essential.

On the Bates, I remember seeing packages labeled “Not for Civilian Consumption.” We were told the items had been irradiated. Some of us asked questions. The response was practical and typical Navy: “You’ll get more radiation standing next to the reactor shielding than you will eating that chicken.”

They weren’t wrong. Our refrigerated storage units were built alongside the reactor containment bulkheads. In that context, irradiated food wasn’t controversial. It was smart and safe.

Today, food irradiation is a well-established intervention in commercial food safety, used for spices, poultry and ready-to-eat meals.

PACKAGING, COLD CHAIN AND HACCP.

The submarine environment also accelerated advances in:

- Retort packaging. Heat-resistant pouches that saved space, extended shelf life and preserved nutritional value better than cans.

- Cold chain management. With no room for error, temperature control was routine and rigorously documented. Galley crews were trained to monitor and verify storage conditions daily.

- Preventive controls. While HACCP wasn’t formalized yet, the philosophy was already in place. On a sub, you didn’t wait for someone to get sick to revise procedures. You anticipated risk, verified controls and practiced responses.

FROM SUB GALLEYS TO SUPERMARKETS.

Back then, we didn’t use terms like “risk assessment” or “corrective action.” We just knew that if the food failed, everything else failed with it.

That lesson has never left me. When I speak about food safety today, I often think of the cooks aboard my sub. I think about the night baker who chose to make bread. And I remember that food safety wasn’t a checklist. It was a lifeline.

Explore the November/December 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- Director General of IICA and Senior USDA Officials Meet to Advance Shared Agenda

- EFSA and FAO Sign Memorandum of Understanding

- Ben Miller Breaks Down Federal Cuts, State Bans and Traceability Delays

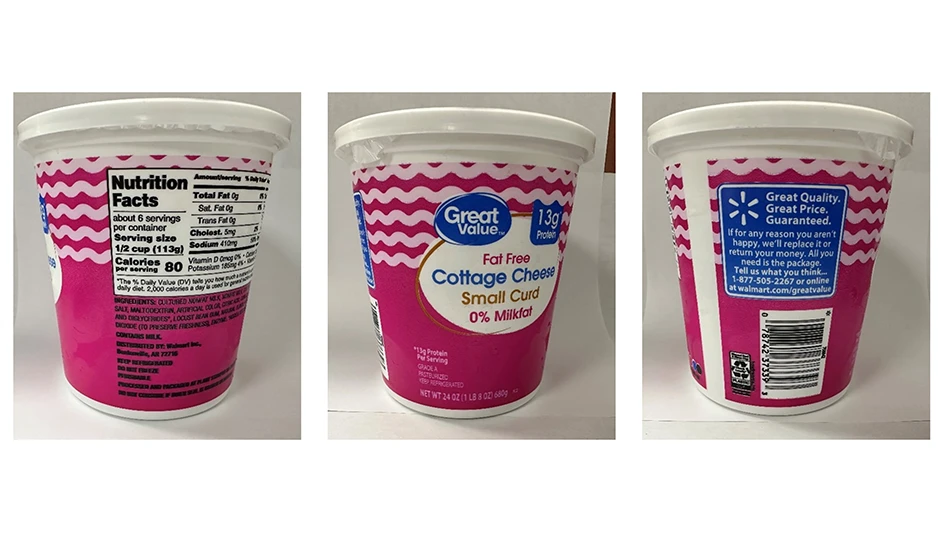

- Michigan Officials Warn Recalled ByHeart Infant Formula Remains on Store Shelves

- Puratos USA to Launch First Professional Chocolate Product with Cultured Cocoa

- National Restaurant Association Announces Federal Policy Priorities

- USDA Offloads Washington Buildings in Reorganization Effort

- IDFA Promotes Andrew Jerome to VP of Strategic Communications and Executive Director of Foundation