Fresh produce is alive. With that fact in mind, proper approaches to the majority of quality and safety issues associated with fresh produce become much more apparent. Keeping produce alive and, to the extent possible, healthy is key to maintaining organoleptic quality. Temperature control, the major factor in achieving these goals, is also useful as a food safety enhancement.

Although we tend to think of fresh produce as a market sector, similar to the bakery and meat sectors, it is perhaps useful to look a bit deeper. Once you have seen a couple of bread or sweet goods bakeries you will understand the general design and product flow in most any other bread or sweet goods bakery you encounter. Likewise, dairy and meat processing operations are generally similar in terms of input, product flow, and equipment. In the fresh produce industry, however, a thorough knowledge of the harvesting, storage, sorting and packing of apples will provide you with little insight into the same processes used to prepare fresh asparagus for the retail market. Knowledge of either of these will prove of very limited value when visiting a large bagged salad producer who may supply a variety of pre-cut products to both retail and food service markets. Fresh produce operations tend to be very product specific from planting through harvest into storage and onto a variety of processes prior to sale.

TIME & TEMPERATURE. Temperature control in fresh produce generally means cold but not freezing, with the exception of tropical products. The temperature range of 32-40ºF optimally maintains the life, health, and quality of most fresh produce. Temperature control is also important for tropicals such as bananas and mangoes, but at higher temperatures. In fact, cooling tropicals to refrigerated temperatures will cause chilling injuries that are very detrimental to quality.

Temperature control is critical to the life and health of fresh produce because it is the major control of respiration rate in products after harvest. It is useful to think of produce as a living entity that is cut off from any source of nutrients at harvest. The quality and shelf life of harvested produce is largely a function of how rapidly available energy, and nutrients that can supply energy, are consumed. A reasonable analogy is to think of harvested produce as an engine with a limited fuel supply. As the fuel is consumed the engine will run smoothly; then, as fuel runs low, it will begin to run rough and finally sputter to a halt. In the case of fresh produce, good quality can be retained until the "rough" stage at which time it will rapidly decline as the item runs out of energy and approaches its demise.

As the temperature of a fresh produce item falls, its respiration rate (the rate at which it consumes its resources) is reduced. An important feature of this phenomenon is its non-linearity. The change in respiration rate over a six degree range, for instance between 32°F and 38°F, is much less than the change between 38°F and 44°F. This non-linear response to temperature is particularly evident for fresh produce in the 35-50°F range. This is exactly the range of temperatures we often find in retail fresh produce displays, with an unfortunate number of them tending toward the high end of the scale. Depending on the specific fresh produce item, the rate of respiration at 50°F can be two to four times the rate at 35°F. Asparagus, for example, is a rapidly respiring item at the high end of the scale where a topped carrot (with the green top growth removed) would tend toward the lower value.

The difference in normal respiration rate and response to temperature is somewhat a function of part of the plant we are interested in as a fresh produce item and the growth phase it is in when harvested. A stalk of asparagus is the rapidly growing structural stem of the asparagus plant. A head of broccoli is the rapidly growing flowering/reproductive portion of that vegetable. These types of fresh produce tend to have very high respiration rates coupled with minimal nutrient storage within the plant structure, a combination that results in an inherently short shelf life following harvest. Producers make great efforts to move these products rapidly from harvest to cooling systems that reduce the internal (known in the industry as the "pulp") temperature to well below 40°F and often to near 32°F.

ADDITIONAL EXAMPLES. Other fresh produce such as carrots, potatoes and apples are, from a botanical viewpoint, reproductive and/or storage structures. Their growth rate is very slow at harvest and their respiration rates are much lower than more rapidly growing structures. These rates can be even further reduced during post harvest storage by controlling temperature and in some cases atmospheric composition. While high respiration rate fresh produce products stretch to achieve a 14 day shelf life, these lower respiring products can be held for months. In fact some varieties of apples and potatoes are held in very precisely controlled storage chambers for up to a year.

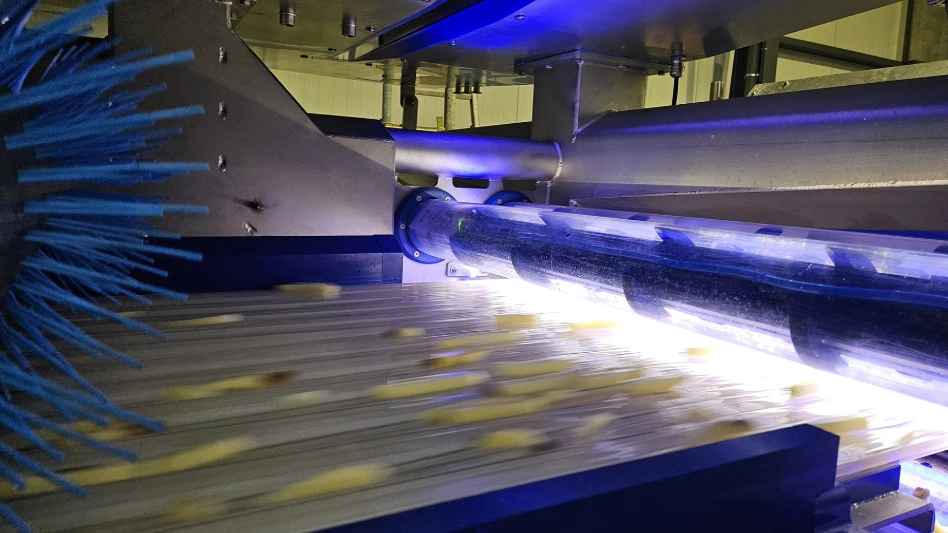

Again, temperature control is the primary key to maintaining quality of fresh produce. This control must start immediately after harvest and be maintained throughout processing, shipping, storage, and display. Several types of cooling systems are used to rapidly reduce post harvest product temperatures. The simplest of these are cold water cascades of various designs. They are generally known as "hydrocoolers" and take advantage of the high thermal capacity of water to rapidly remove heat from products, such as asparagus, that are not damaged by exposure to water and the small amounts of chlorine normally added for sanitation.

Some products, such as strawberries, are susceptible to disease if wet and are too delicate to endure hydrocooling water flows without damage. Such products are cooled in "forced air" systems. These systems are designed to pull cooled air in very large volumes through stacked boxes of product. Care must be taken with regard to the temperature of the incoming air to prevent freezing. These systems also generally have some method of hydrating the incoming air in order to reduce evaporative moisture loss from the product.

Vacuum cooling of fresh produce uses a very high vacuum to reduce the boiling temperature of water to the point that it actually cools the product as it vaporizes. This works very well for some products, especially iceberg and other lettuce products. Vacuum systems are called "tubes" in the produce industry as they are commonly a large diameter tubular structure capable of holding four to eight pallets of boxed product.

Ice injection systems use a sealed chamber to contain a pallet of boxed product, such as broccoli, while a pressurized slurry of ice and water is forced through specially designed vents in the boxes. As the slurry flows, ice is deposited in voids within the product in each box. As the iced, boxed product proceeds through storage and shipping it will continually drip water due to melting. This is an effective method to cool some products. Products cooled in this manner may give some indication of temperature abuse, seen as excessive melting of ice, later in the shipping and storage system. They also make a mess throughout transport and storage and require waxed cartons that cannot be disposed of through normal channels.

All of these methods have been developed to ensure that fresh produce can be cooled rapidly in conditions appropriate to the specific product. Once fresh produce has been cooled to temperatures conducive to extended storage, it is critical to maintain the "cold chain" throughout shipping and storage. There are a number of recent innovations in fresh produce handling intended to maintain product quality over an extended shelf life. Most of these are related to placing fresh produce in bags or other containers made of materials that influence the gas composition of the atmosphere within the package. These packaging systems generally provide some benefit as long as product temperatures remain in an appropriately cold range. If fresh produce is allowed to warm above normal refrigeration temperatures, its respiration rate will increase and the value of exotic packaging will be largely lost.

CONCLUSION. There are two sayings in the fresh produce industry. "Sell it or smell it" refers to the perishable nature of the product. The other saying states that there are three primary concerns in maintaining fresh produce quality, "Temperature, temperature, and temperature." These sayings encompass the two most critical issues in providing quality fresh produce to the market: time and temperature. Across the wide variety of products, sources, and processes that make up the fresh produce industry, firm control of time and temperature is a primary requirement for success. AIB

The author is Vice President Operations at Sholl Group. His e-mail address is adavis@sholl.com.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- FDA Releases Produce Regulatory Program Standards

- Invest in People or Risk the System: Darin Detwiler and Catalyst Food Leaders on Building Real Food Safety Culture

- USDA Proposes Increasing Poultry, Pork Line Speeds

- FDA Releases New Traceability Rule Guidance

- TraceGains and iFoodDS Extend Strategic Alliance

- bioMérieux Launches New Platform for Spoiler Risk Management

- SafetyChain Receives SOC 2 Type 2 Certification

- Puratos Acquires Pennsylvania-Based Vör Foods