Shortly after changing suppliers, the food plant began to have problems with tears in its packaging. The solution, or at least the source of the problem, would seem to be fairly evident, except that the plant hadn’t changed its packaging supplier; rather it had changed an ingredient supplier.

As chief packaging specialist at the Packaging Science Center in Minneapolis, Minn., D’Juana (DJ) Ballard sees cases such as this on a regular basis and says that an ingredient change is a frequent cause of packaging issues. In this case, the problem was caused by a change in garlic type; where the plant had previously purchased a shaved product ingredient, the new supplier was providing a garlic nugget. Packaging material that had been sufficient in the past was now being torn by the jagged edges of the nugget. “With a neutral change like that, too many plants never consider the impact it could have on anything else,” Ballard says. “They don’t realize that the ingredient is incompatible with the material they have selected.”

Product/package incompatibility can be compounded in larger plants when separate groups are responsible for the product and packaging. For example, if a QA manager thinks an ingredient change is neutral, she may not think to inform those working with the packaging that a change has been made. When a problem arises, no one may ever link the new ingredient with the issue. On the other hand, the packaging procurement group may decide to change the liner grade of a carton to provide a cost savings — but because it was a minor change, they may not have thought to mention it; or a supplier may make a slight material or process change which causes repercussions at the plant, such as equipment jams from insubstantial material, structurally inadequate packages that allow products to fall out, and product contamination such as odor absorption or off flavors. All materials have threshold values below which they can be affected by or affect products or equipment, Ballard says. “If you go below (the threshold), that package may no longer perform like you need for it to perform.”

It is for these reasons that one of the first questions Ballard will ask when working with a plant is “Have you changed anything?” to include packaging material or component, packaging supplier, and ingredient or ingredient supplier. In the case of the garlic nugget, the plant had consulted with its packaging supplier before calling Ballard, but they couldn’t resolve the issue because the supplier was addressing the material, not the total system. “That’s what we do,” Ballard says. “We look at the total system.”

GROWING COMPLEXITY. “One way of looking at it is that packaging originally started off as a means of being able to contain the material for protection, storage and transport,” says Ralph Calvert, technical specialist – gas chromatography for Intertek Caleb Brett. “Only later on did it become a means of branding, attracting, longer preservation and advertising. The more complex the packaging has become the more potential there is for problems at every stage.”

In fact, it was to address the ever-growing challenges of physical product damage and short shelf life that Michigan State University opened its School of Packaging in the early 1950s. Packaging was still a developing industry, and “we weren’t seeing a lot of science behind it,” says Professor Bruce Harte. Since then the school and the packaging industry have both become multi-faceted, with packaging becoming more important for protection, utility and convenience and more complex in design — with every material type unique in make-up and product compatibility. As an example, the school began to devote more of its efforts to plastics packaging in the ’80s, an era of significant growth for the material in food and beverage packaging. But ensuring the plastic would hold the foods without leakage was only half the challenge; in addition, testers had to ask, and resolve, such questions as “How many of the flavor components in a product would be absorbed by the packaging material?” “Would the plastic diminish the product’s quality or affect shelf life?” “Would an affect vary with larger or smaller amounts of a flavoring?”

The effects of packaging on a product can have a number of deviations, and, Harte says, “It’s a continuing issue even today as plants change materials or even designs.” Harte recommends that plants take eight aspects into consideration when seeking new or redesigned packaging:

1. Ensure the material is approved for food-contact use and specifically for the intended use, and that it follows all government regulations.

2. Select a packaging that will satisfy the consumer, considering convenience, product visibility and attractiveness as well as strength of packaging to avoid damage.

3. Choose a material that affords physical and chemical protection for the product.

4. Ensure the design works with your manufacturing, handling and transportation systems.

5. Confirm that the material provides an adequate packaging barrier.

6. Test the material for product compatibility.

7. Ensure it meets all physical property requirements.

8. Consider the cost-effectiveness of the material and the design.

Another area plants should consider is slack fill, Ballard says. “Make sure the package is not grossly oversized for the contents of your package.” This may come into play when plants look for ways to save on packaging component costs by harmonizing sizes, or to avoid equipment down-time for change-overs or when the marketing group wants to increase the package size for “billboard effect,” and doesn’t consider regulations which limit the size of the product’s package in comparison to its contents. “There are debates about how far you can go with it,” she says. “Just be sure you’re not intentionally misleading the consumer and that you consider the potential for unintended product damage.”

QUALITY PERCEPTION. Selecting packaging that will satisfy the consumer is more important than is realized by many quality assurance managers. “People marginalize packaging as compared with how they view the product,” Ballard says. “But I think the packaging truly is the most important part.” To illustrate her point, Ballard says to think about your own shopping habits. If the packaging of the product you wish to purchase is damaged, do you take it anyway, or do you — like most people — push it aside to find one which is intact? And if, in pushing the product aside, a shopper finds that all the products are similarly damaged, will he choose to purchase a different brand instead, and leave that store with the perception that your product is of inferior quality?

“Marketing is about obtaining the consumer’s attention,” Ballard says. But damaged packaging can affect the consumers’ perception of the quality of the product itself, and “marketing becomes insignificant in one moment.”

TESTING & COMPATIBILITY. When working with a consultant on package design, plant management should come to the table with goals in mind: “This is what we want to accomplish; this is our goal and objective,” Harte says. “We then help design the test to generate the information you need.”

Once the consultant or test site has complete information on your goals, objectives and product, it can begin to test materials for compatibility and potential issues. Tests will generally include analysis of individual components within the product using equipment such as electrobalances and chromatographs. The equipment, Harte says, enables the tester to measure the amount of a component that may be coming out of a product and its effect upon a material. The sensitivity of the equipment also enables measurements of individual components to minute levels for such things as temperature, relative humidity and interaction on testing materials.

Calvert works primarily with chromatography focused on taint or odor problems with packaging. His work and publications provide detailed but simple explanations of the science behind the product/package compatibility and testing, with a key focus on incompatibility issues of odor and taint. “These usually start with the deceptively simple question, ‘What?’ inevitably followed by when, where, how and who. And contrary to the impression given by the CSI television series, you don’t put a sample in a machine and get a complete answer in 10 seconds,” Calvert said. (See article “Finding the Incompatible Component” at right for an in-depth look at one form of product/package testing.)

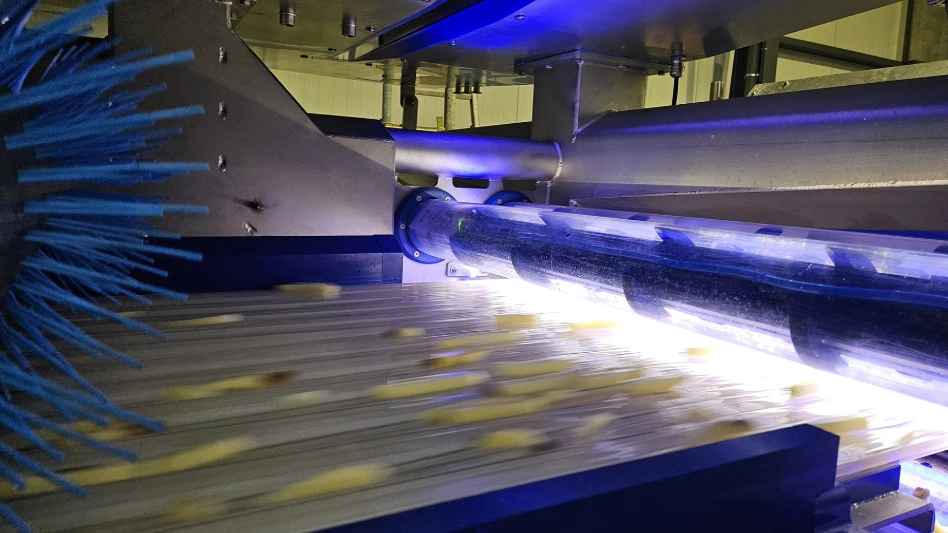

PACKAGING EQUIPMENT. In addition to consideration of the product and packaging materials, plants need to assess their packaging equipment and process to prevent packaging problems. Ballard identifies cross contamination and equipment capability as two potential issues. The industry as a whole focuses on allergen cross contamination and does a good job with labeling, Ballard says, but doesn’t do so well in preventing contamination in downstream equipment. “We’re using the same packaging equipment to package product for food-allergen and non-food-allergen products, but we’re not doing enough in how we clean,” she explains.

Equipment capability becomes an issue when the upstream process produces more product than the downstream equipment can sufficiently handle, she says. If equipment is forced beyond the capabilities for which it is designed, the packaging is compromised, resulting in issues such as misaligned sealing surfaces or particulates caught within sealants, decreasing the package strength and potentially impacting shelf life.

Changes in any aspect of a food or beverage processing plant can have unexpected repercussions even when the change is thought to be neutral, and the interrelation of a product with its package means such changes can have far-reaching effects. “The most important thing to be aware of is what that packaging is contributing to the product,” Harte says. “Know something about your packaging. Take the initiative to train yourself or get training.” And if you do have a problem, start with your packaging supplier, then remember Ballard’s key question: “Have you changed anything?” QA

The author is a contributing writer to Quality Assurance & Food Safety magazine.

Explore the August 2005 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- FDA Releases Produce Regulatory Program Standards

- Invest in People or Risk the System: Darin Detwiler and Catalyst Food Leaders on Building Real Food Safety Culture

- USDA Proposes Increasing Poultry, Pork Line Speeds

- FDA Releases New Traceability Rule Guidance

- TraceGains and iFoodDS Extend Strategic Alliance

- bioMérieux Launches New Platform for Spoiler Risk Management

- SafetyChain Receives SOC 2 Type 2 Certification

- Puratos Acquires Pennsylvania-Based Vör Foods