Stored product insects are a major challenge in food plants, but through the award-winning work of Research Entomologist Jim Campbell, these enemies lose ground with each proposal, project and publication produced by this highly respected research pioneer.

Campbell is a research entomologist with the United States Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and an adjunct associate professor with the Kansas State University Entomology Department, both located in Kansas. Earlier this year Campbell was recognized for his pioneering research on stored product insect behavior and ecology and its application to improving integrated pest management in food facilities, receiving the 2004 ARS Early Career Research Scientist of the Year Award for the Northern Plains Area. The award is given to commend the creative efforts, scientific leadership and major research achievements of ARS scientists. Campbell’s research focuses on “how we can gain a better understanding of insect behavior and how we can use this for pest management,” Campbell says.

Understanding the behavior of stored product insects in food processing plants and food and storage facilities enables the development of better techniques and tools to fight the pests, Campbell says. How far can and will an insect travel? Are they coming from outside or were they brought in with a delivery? What are the critical points in their biology? “We may not be using the most effective management application if we don’t understand those processes,” he explains.

Campbell got interested in entomology working in the lab as an undergraduate at Rutgers University, after which he went on to attain his M.S. in Entomology, then continued to pursue his studies, gaining a Ph.D. in Entomology from the University of California, Davis. Since starting with USDA in 1999, Campbell has conducted research and achieved breakthrough findings in such areas as the use of spatial information from pheromone trap monitoring for making pest management decisions; fumigation impact on stored product insects in a grain-processing facility; stored product insect management in flour mills; and response of stored product insects to food odor emanating through packaging.

IN-PLANT RESEARCH. For some of his research, plant managers have allowed Campbell to work directly in their food processing facilities, where he concentrates on understanding the biological processes of the pest species in the plant, developing tools for management and evaluating the effectiveness of existing programs. Such research is invaluable and of mutual benefit, he says. “We are able to provide [the plant] with detailed monitoring, and it helps us because it is difficult to do research applicable to the food industry without going out and doing it there.”

One of the evaluations Campbell conducts is the effect of the pest management program on insect populations, not only whether they are controlled or eliminated, but also how quickly they rebound, with a goal of finding ways to manipulate and impede the rebound. Campbell seeks to learn: Is there a trend? Can the time between treatments be extended without affecting control? If you make a change to the program, does this improve it or make it worse? If a problem is found but a plant can’t be shut down immediately, what can be done in the interim?

Campbell takes his research beyond the basics, not just monitoring pheromone traps and charting results, but also establishing all factors that may influence trap counts, interpreting data and clarifying what the data really means. For example, does a high count mean that a pest program isn’t working; or is it showing the seasonal variations of a pest which is entering the plant from outdoors? It is in such areas that the understanding of an insect’s behavior and movement becomes so critical, and that Campbell’s “tireless” study is evident and effectual. “One aspect of working with Jim is that he is a true scientist and refrains from reaching conclusions until he is satisfied that all pertinent data has been collected. There are no quick conclusions on his part,” says Al St. Cyr, AIB Head of Food Safety Education. “He is very well regarded in the food industry as well as among his scientific peers. His credibility and integrity are beyond question.”

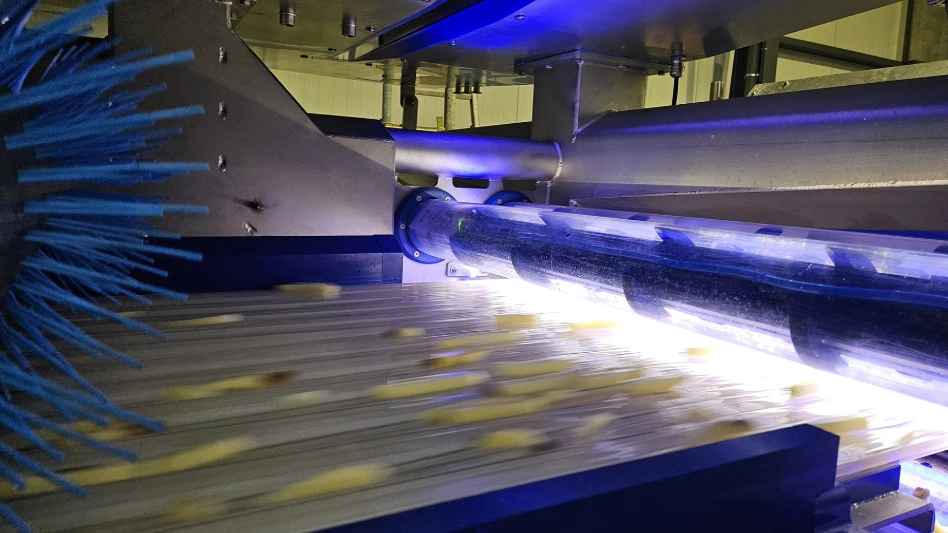

One food processing-related study Campbell has conducted is on the response of the sawtoothed grain beetle to food odors emanating through packaging films, the findings of which, as stated in the report published in Environmental Entomology, “indicate the necessity for improved package designs and better sealing and handling methods to prevent flaws in packaging through which insects may enter.”

There are two key issues associated with packaging, as relate to stored product insects, Campbell says. One is that some species can chew into packaging, but this is really a small percentage of pests. “The vast majority of ways insects get in is because they find a route in,” he explains. “We’ve shown that even with a good odor barrier, if there is a small opening, the insect will still find it.” Openings can result from the way the package is manufactured or by flaws or openings introduced in the handling of the packaging. The packaging study shows how easily insects are able to find ways into stored products, Campbell says. In fact, if a female beetle cannot work its way into an opening, she will insert her ovipositor into the opening and lay her eggs. “Even small holes can be exploited by insects,” he says.

Almost any packaging can be penetrated by an insect — unless it is something like a can, Campbell says, but “the goal is really to try to reduce the rate at which that can happen.” To do so, identify the holes that are necessary in a package, such as those needed for ventilation, then ask, “What can be done to try to make it more difficult for the insect to get in?” If openings are needed, convoluted pathways can be integrated, such as vents in one location on an inner layer and in another location for an outer layer; if the product doesn’t need to be vented, packaging should incorporate the best seal and odor barrier possible and be made of strong, resistant materials. Campbell advises that plant or QA managers study their packaging in terms of previous problems then work with the plant’s manufacturing process to prevent future incidents.

THE PLANT’S ROLE. While Campbell’s research concentrates primarily on insect behavior, the results of pest management in a plant also can be greatly affected by the behaviors of plant managers and workers. “A lot of it is in the realm of the plant manager — making the environment less favorable for the insects to live,” Campbell says. “Stored product insects are pests because they do well in the environments we’ve made.” It is the insect’s behavior and ability to get into plants and find and infest stored products that make them pests, and plant managers need to be sure they are getting the right information from their pest management supplier, including what the pests are, how and where they are finding niches to live and access to food packaging, and detailed recommendations for managing the populations. “It needs to be an interactive process,” Campbell says. “Plant managers need to think about that food plant as an environment for insects and the fact that they have the power to manipulate that environment to make it less favorable.”

The many variations among plants make it difficult to generalize or say one pest management technique or tool is best. But, he says, you can implement a monitoring program to show how pests are distributed through the building and gain some insight on how well the current management program is working. It’s also important that plant managers understand what is being done by the pest management technician and why, so they know if they are getting good value, Campbell adds. Because there is a range of services that technicians provide, he explains “it’s helpful for them [plant managers] to know what to ask for.”

CONTINUING CONTRIBUTIONS. “There is always more to learn on this,” Campbell says, and his drive for learning has elicited more than $400,000 in grant support from sources such as the National Science Foundation, the Environmental Protection Agency and USDA, as well as commendation from AIB’s St. Cyr. “Dr. Campbell’s contribution in the area of basic and applied research has had a significant impact on our understanding of the behavior of several species of stored product insects,” St. Cyr says. In particular, he notes Campbell’s ongoing work on lesser grain borers as very important to those who store grain and his trap and release studies as revealing important data about the mobility and movements of the Indian meal moth and warehouse beetle through food plants.

Campbell’s work has not just expanded his own learning; it has augmented understanding across the academic, pest management and food processing fields. Campbell routinely gives lectures in entomology, trains student researchers, publishes studies, and works directly with food plants and facilities. More information on Campbell’s work and copies of his publications are available at http://bru.gmprc.ksu.edu/sci/campbell/.

As described by St. Cyr, who is himself considered to be an industry authority, “He has expanded my knowledge and allowed me to be a conduit for some of the applied research he has completed that most benefited the food industry segments I work with.” Research that will live on through generations: “I would anticipate that these young researchers [whom Campbell has led] will themselves provide valuable research in the future because of the opportunity to work with Jim.”

The author is a contributing writer to Quality Assurance & Food Safety magazine.

Optional Readouts

“Plant managers need to think about that food plant as an environment for insects and the fact that they have the power to manipulate that environment to make it less favorable.” – Jim Campbell, research scientist, USDA Agricultural Research Service

Sidebars

Lesser Grain Borer

· Approximately 1/8-inch long

· Cylindrical

· Dark brown in color

· Head tucked underneath prothorax and not visible from above

· Larvae develop within kernels of whole grains

· Female lays 200 to 500 egg in her lifetime

Sawtoothed Grain Beetle

· Approximately 1/10-inch long

· Dark brown in color

· Long, flattened beetle

· Six saw-like teeth on each side of the prothorax

· Smaller eyes than the merchant grain beetle

· Larvae yellowish/white with a brown head

(Source: PCT Field Guide for the Management of Structure-Infesting Beetles)

Explore the August 2005 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- FDA Releases Produce Regulatory Program Standards

- Invest in People or Risk the System: Darin Detwiler and Catalyst Food Leaders on Building Real Food Safety Culture

- USDA Proposes Increasing Poultry, Pork Line Speeds

- FDA Releases New Traceability Rule Guidance

- TraceGains and iFoodDS Extend Strategic Alliance

- bioMérieux Launches New Platform for Spoiler Risk Management

- SafetyChain Receives SOC 2 Type 2 Certification

- Puratos Acquires Pennsylvania-Based Vör Foods