If you listed Salmonella, Campylobacter or Norovirus as numbers one to three — in any order, give yourself three points. If you listed E. coli or Listeria as top causes, subtract three points. As for those bonus points, it just depends on which list you read.

There are a number of challenges in tracking causes of foodborne disease, one of which is that many incidents go unreported, as diagramed on the Burden of Illness Pyramid (right). The sufferer writes it off as flu or doesn’t seek care, the doctor doesn’t take a specimen, the specimen is not tested for the appropriate disease, or the lab does not report the case to the health department. “Traditionally the health department data is just the tip of the iceberg,” said Tim Jones, deputy state epidemiologist for the Tennessee Department of Health and director of FoodNet in Tennessee. Any outbreaks or even individual cases identified at this point probably represent a much higher number of incidents.

FoodNet, the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, is the principal foodborne disease component of CDC’s Emerging Infections Program (EIP) and is a collaborative project of the CDC, 10 EIP sites, USDA and FDA. FoodNet conducts active surveillance for foodborne diseases and related epidemiologic studies.

To attempt to develop a better calculation of actual incident rates, FoodNet is currently working on studies to estimate the percentage of decline associated with each step in the pyramid. Take, for example, Campylobacter which is known to cause a high percentage of reported foodborne illness, but ranks differently in each list of common pathogens. When health department reports are analyzed, “the rates of Campylobacter around the country are just widely inconsistent,” Jones said. Because no one can be sure which step — or steps — in the pyramid are effecting this inconsistency, the group is taking proactive steps, visiting, surveying and auditing labs to check specimens, determine if the labs are even receiving test specimens or perhaps are not testing well for it.

Many of the pathogens which cause foodborne disease, including Campylobacter, don’t have commercially viable test methods, while other pathogens aren’t even yet known, said Timothy Biela, Vice President of Food Safety and Quality Assurance and Chief Food Safety Officer for Texas American Foodservice Corporation, Fort Worth, Texas. As a result, it is those pathogens which can be tested simply and cost-effectively that receive the most attention — such as E. coli, Salmonella and Listeria. The test for Campylobacter is a very, very difficult microbiological test, Biela said, although studies continue to seek simpler methods, asking, “How do we actually test or screen for the pathogenic strain of Campylobacter, so it is cost effective and easy to use?” On the other hand, laboratories and even plants themselves test for Listeria, though it causes less than one percent of foodborne illness, in part, because it has very well defined, commercially available test methods which are easy to apply and because of its high-profile outbreaks. (See “Product Specificity” section below for more on Listeria.)

The challenges extend even to governmental agencies which don’t, or can’t, require testing for pathogens which do not have commercially viable methods. CDC itself notes this complexity in such statements as that included on the disease information page of Vibro parahaemolyticus. This is a common cause of foodborne disease in Asia, the web page notes, but is less so in the U.S. This is not, however, due to any advanced science or technology in the U.S., rather, the description says, “It is less commonly recognized as a cause of illness, partly because clinical laboratories rarely use the selective medium that is necessary to identify this organism.” And, because all states don’t require that the infections be reported to the state health department, it is difficult to track incidents.

PRODUCT SPECIFICITY. Another challenge in defining the most common pathogens about which plants need to be concerned is the fact many pathogens are product specific. “Every food is different and every plant is different. Raw commodities, ready-to-eat, ready-to-cook food cannot be generalized,” Biela says. “Each individual company needs to pay attention to its product and utilize its experience to tell what specific pathogens are.

“However, the list showing CDC data are the (pathogenic bacteria) we are aware of today that are causing illness in the human population,” Biela adds. “I think there are lots of organisms that we haven’t defined as causative agents.” Pathogens which he believes will be defined as such in the future, once labs get into genetic microbiology as there is a great deal of transfer of pathogenic genes between particular bacteria groups today and once we begin to better understand and utilize the epidemiological data generated by groups such as CDC’s FoodNet, to actually research and define these agents.

One of the reasons that particular pathogens get more attention though they rank lower on common cause lists is because a single incident can have wider-reaching effects. For example, Jones say, “Campylobacter is interesting because the number of Campylobacter cases that are reported is almost the same as Salmonella, but most of those are sporadic. You very rarely have a Campylobacter outbreak.” For that reason, it is much less of a worry for processors. “Salmonella is going to nail them much more often.”

In addition, Listeria, Salmonella and E. coli pathogens have high death-association rates with one of five people who are diagnosed with clinical Listeriosis dying from it, and more than 60% of foodborne-illness-associated deaths in the U.S. due to Listeria (28%), Salmonella (31%) and E. coli (3%), states Dr. Morgan Wallace of DuPont Qualicon, citing the “Food Related Illness and Death in the U.S.” article by Mead et al. in Emerging Infectious Disease, September-October 1999.

“Listeria is a huge challenge,” Jones says. “It’s a nightmare for a plant.” This is because Listeria is common in the environment and it has incredible reproductive capability. “Once it gets in a plant, in the environment, it’s very difficult to get rid of.” Listeria is also frequently in the news and in recalls. This is most likely, though, because the outbreaks which do occur are high profile and Listeria is high on the list of pathogens which are looked for in plant environments. There are probably more Listeria-related recalls because inspectors are looking for it, and catching it, he says.

In actuality, he adds, “Listeria is everywhere. In one-third of American refrigerators — if you look hard enough, you’ll find it.” Which raises the question: “If Listeria is in one-third of all our refrigerators, and we’re all exposed to it frequently, why are so few people getting sick?” Jones asks. “You and I probably ate it last week.” This is not to say, however, that Listeria should be ignored as it does raise concerns for its high case fatality rate and the threat it poses to high-risk populations, including pregnant women.

In fact, the attention given to Listeria, and other low-ranking pathogens may be a reason for their low-incident rates. Because tests are commercially viable, plants know that inspectors will test for Listeria, and it is such a “nightmare” that plants are more proactive in fighting the pathogen and preventing its build-up. “I think the attention the industry gives to it is definitely making our food supply safer,” Jones says.

WHAT CAN YOU DO? With every plant being unique, and susceptible to different pathogens, it is important that plant and quality assurance managers seek to learn as much as possible about those which are most relevant to your product. It is important that you understand the broad scope of the product, how to apply the strategies and develop the platforms for food safety initiatives, Biela says. “You need to know about everything you can — and everything you don’t know.”

But despite the differences between plants and relative pathogens, there are common steps plants can take for detection, prevention and reduction.

To reduce pathogen risk in their plants, Biela says, plants should utilize HACCP programs and industry best practices, such as those for the beef industry found on the website of the Beef Industry Food Safety Council (www.bifsco.org). Other things plants can do, he says, “Create a defined set of best practices for your processes based on sound science, and then measure your results, analyze the data and continually reassess and reset your targets and goals.”

Although many of the most common foodborne disease pathogens are transferred at the final point of food preparation, such as in the home or restaurant, occurrences can also result from handling in food plants, particularly direct-to-public plants such as bakeries and those at which ingredients are not cooked. This is because a high rate of transmission is caused by a lack of employee cleanliness, for the most part, those who are or were recently ill.

Jones notes two primary reasons that plants are less susceptible to this form of transmission:

• some incidents early in the food chain will be resolved through cooking of the product. For example, norovirus bacteria, which is very difficult to kill, will be killed through cooking.

• food plant employees are more likely to be full-time workers with sick leave benefits, whereas many restaurant employees are part-time, without such benefits, so they continue to work even when they have illnesses which can transmit such bacteria.

But because food handling is a primary cause for outbreak, plants should take basic precautions. One of the most effective methods of reducing pathogen risk, whether in a bakery, restaurant or food processing plant, is also the simplest: employee cleanliness and hand-washing. If you read through the CDC descriptions of the top foodborne diseases and causes, including that for Salmonella, you soon realize that one line is included, with some variation, in the description of causes for almost every disease listed: “Food may also become contaminated by the unwashed hands of an infected food handler, who forgot to wash his or her hands with soap after using the bathroom.”

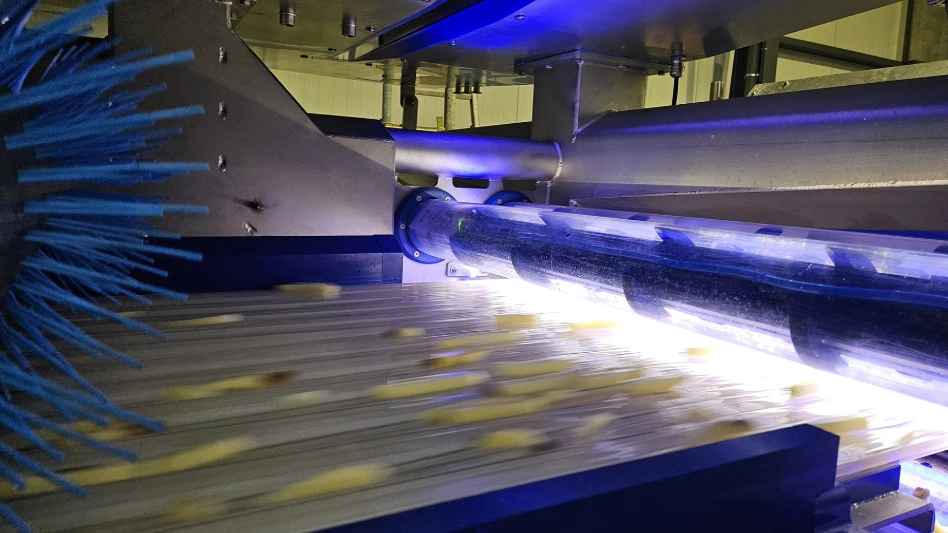

IRRADIATION. Though still a controversial application, irradiation can help plants fight and reduce pathogen contaminants. While irradiated food is available, it is not yet completely accepted by the public, or by industry experts. Jones is an avid supporter of irradiation for food safety. “I really think that food irradiation is going to be a very important tool to take us to the next step of food safety,” he says. “There are lots of incidents where the kind of food outbreaks we’re dealing with can be avoided by irradiation.”

The problem with irradiation is more one of marketing than efficacy, Jones believes. The public is afraid of irradiation, he says, but in fact “you can relate it in many respects to the pasteurization of milk.” When pasteurization was first proposed, many of the same arguments were used against it as are now being heard against irradiation. Now, pasteurization is a common and accepted food-safety process.

And if you are starting to hear the words “cold pasteurization,” don’t be fooled. It’s simply another term for irradiation — one that many are hoping will reduce the fear inherent in any term with the word “radiation” in it.

Biela sees a place for irradiation, but feels it has limits. “I think, in a lot of foods, it has its applications,” Biela says, “but it’s not a silver bullet.” Irradiation, he says, is not a very palatable option for beef. In such high-fat foods, the dose of irradiation needed to kill the bacteria would affect the taste and palatability of the meat. “You wouldn’t enjoy it if you ate it,” he says.

IF YOU HAVE AN INCIDENT... “It’s very painful for a food processor to work with an outbreak,” Jones says. When an outbreak is traced back to a food plant, many plant managers become defensive, don’t want to share plant processes or secrets, or deny the allegation altogether. But the best thing the plant can do is cooperate and work with investigators to reach quick resolution. “When companies bite the bullet, are open with investigators and share their records, in the end, it’s less painful for everybody.”

While food producers need to do everything they can to ensure the food leaving their hands is safe, a great deal of it comes down to the consumer. “There’s only so much that health departments and the industry can do. No matter how many times we tell people to cook ground beef, 20 percent still eat it pink.” In addition, Jones says, 20 percent of people don’t wash their hands after handling raw meat, 20 percent don’t wash the board after cutting raw meat, and 50 percent eat undercooked eggs.

“The industry can do everything it wants to have pathogen-free food, but nothing is perfect. But,” Jones adds, “that doesn’t mean we give up.”

Even with all the unanswered questions, as-yet unknown pathogens, economic hurdles and general challenges in pathogen detection, prevention and reduction, the United States is tremendously successful in its food safety efforts and public-health protection, Biela says. “We continue to lead the world in food safety.”

The author is a contributing writer to Quality Assurance & Food Safety magazine.

Explore the August 2005 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- FDA Releases Produce Regulatory Program Standards

- Invest in People or Risk the System: Darin Detwiler and Catalyst Food Leaders on Building Real Food Safety Culture

- USDA Proposes Increasing Poultry, Pork Line Speeds

- FDA Releases New Traceability Rule Guidance

- TraceGains and iFoodDS Extend Strategic Alliance

- bioMérieux Launches New Platform for Spoiler Risk Management

- SafetyChain Receives SOC 2 Type 2 Certification

- Puratos Acquires Pennsylvania-Based Vör Foods