The advances in technology are proving to be a boon for tracking and traceability within the food chain. Not only are systems continually improving and expanding their functionality, but the costs of the systems are dropping, and new technologies are emerging, bringing entirely new systems and uses to light.

According to a publication from USDA’s Economic Research Service, "Traceability in the U.S. Food Supply" (2004), the original establishment of traceability systems was market driven with three primary motives: supply-side management, product differentiation, and food safety and quality control. Because the motives have served to convey associated benefits for food suppliers, such as lower-cost distribution systems, recall costs and liability expenses, and increased sales and brand equity, it has led to further development of tracking and traceability systems.

Some of the most recent technological developments and breakthroughs that are impacting the links of the food chain include continually improving, Web-enabled, supplier-integrated supply chain management; continually expanding – and increasingly retailer-required – RFID tracking; automated temperature control and tracking; and real-time, automated recall and incident alerts.

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT. "Even the simplest products have very complex supply chains," says Tom Deeb, executive consultant, ASI Food Safety Consultants, St. Louis, Mo. "It’s not only the foodstuffs, it’s the food packaging" … and the label printing, the transportation, the distribution and so on. If it were just a matter of knowing the supplier names and contact information, it might not be so complex, but when you figure in a processor’s need to assure that suppliers conform to its quality, safety and security requirements, the complexity grows.

Processors have used a variety of systems to try to manage this complexity – from Excel spreadsheets to extensive electronic data systems. But now technological advances have not only eased the complexity but have made systems cost-accessible to virtually any plant, Deeb says. Data-transfer technologies, such as Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), have been around for a long time, but it was the advent of Java and the .NET frameworks that have brought supply chain management to a new level. "It’s only in the last couple years that we have had the technology that allows suppliers to input their data and allow data sharing," Deeb says. "Most were not available in an affordable format before this decade."

The systems differ from those of the past in that they’re not just portals, Deeb explains. They go beyond basic data collection and exchange, allowing for attachments (such as audit reports or photos), trending and analysis. The systems, he says, "took advantage of the Web and how it can be used to exchange information between partners." And with these advances, and software and equipment accessibility, "there’s no reason today that [suppliers] should not be able to work within your system."

This integration provides a number of benefits to the food processor:

• Audit reports – rather than reading through entire reports to find the 10 details or two areas of non-compliance important to the Quality Assurance manager, the software can be customized to track for and highlight these items. "You no longer have to thumb through – either electronically or by hand – pages and pages of information," Deeb says.

• Third-party auditing partnerships – better yet, you could integrate your auditing agency into your system so they review and highlight for concerns or corrective actions, then track them to ensure closure.

• Trend tracing – data can be traced by region or type of supplier to show trends in key performance indicators, ongoing non-compliance, or other variables of importance to QA professionals.

• Analysis and action – data collection is simply the first step. With the trending and analysis capabilities of the newer technologies, plants can customize their program for analysis of specific criteria on which action can then be taken for improvement.

• Validation and verification – the information input by supplier should always be validated by audits, photographs, visits, etc. The results of such validation can then be integrated into the supplier’s profile to enable ongoing monitoring, comparison and assurance of compliance. The system’s functions can quickly tell you whether the recent rodent issue is indeed a one-time occurrence, or if it has shown up repeatedly during inspections; you can track compliance to ensure that identified issues are corrected; you can trend individual suppliers to determine your best and eliminate any that cause concern.

Implementation of an electronic, integrated quality and safety supplier management system can be as basic as a 30-day, virtually off-the-shelf solution, or as extensive as a completely customized program — with the price tag generally equating to the amount of customization. This means you may need to somewhat adapt your processes to a system, rather than expecting the system to completely integrate into processes you already have in place. A processing plant should seek a vendor, however, who asks the quality questions themselves; that is, the supplier should have a firm understanding of the plant’s needs, processes, people, goals and budget before making a recommendation. Other things to consider:

• Security – "Security is and should be a concern for the companies," Deeb says. Discuss the vendor’s provisions for firewalls and hacker-prevention, as well as options for internal user securities. Most programs will have sensitive information that companies don’t necessarily want everyone in the organization to know. Ask about areas such as view rights, delete and add rights, and other such general and administrative user options.

• The "right" data collection – "Anytime you can collect and analyze data, make sure you’re collecting the right data." Focus on the areas most important to your business, Deeb explains. If a manager says, "I’d like to produce reports on XYZ." Ask, "What are you going to do with that information, and why is it important?"

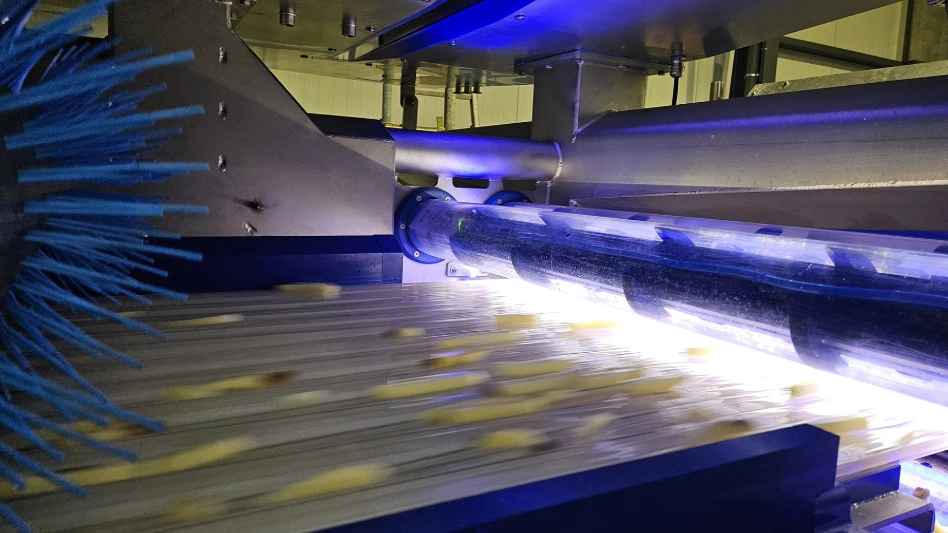

RFID. The use of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) in the food chain is not a new application. In fact, it was used during the Mad Cow scare of 1989 when Texas Instruments (TI) developed an RFID tag to track livestock in Europe. Today, RFID is still used to tag livestock – most recently attaining support from USDA for integration with livestock ear tags used in its National Animal Identification System (NAIS), but it is also increasing in use for general product or package tracking to the point that some major retailers are requiring its use by suppliers, and tracking systems, which in the past were often prohibitively expensive, have become accessible.

RFID systems are beneficial because they provide labor savings and help move products more quickly along the chain, says Bill Allen, director of strategic alliances, Texas Instruments. This is particularly true for perishable items where producers were looking for ways to reduce touch labor and speed products through the supply chain more quickly, he explains. RFID also enables increased asset tracking, especially for returnable containers, such as fruit and bread cases and even beer kegs. Breweries have long had trouble with these high-value returnables. Allen provides, as an example, the practice of unscrupulous vendors refilling empties with unbranded beer and selling them as a name brand, or simply stealing the kegs and melting them down for their metal. With RFID tracking, the accountability is raised, and traceability on the kegs is increased.

While tracking with scanners and bar coding certainly has its place, RFID can provide a time savings when the goal is to track items through the system. Allen provides the example of a producer with regular distribution of 24-case trolleys. "They used to spend an inordinate amount of time reading each bar code, scanning each, than regenerating a code if one couldn’t be read," Allen says. With the RFID system, a portal was built. The trolley would be walked through the portal and "within seconds," he says, "it would read all 24 cases on the trolley."

RFID systems also can speed up the ability to track a product back to its origin and enable tracking of length of time spent at each location in the chain – traveling, in the distribution center, on the shelf, then sold or destroyed. "RFID provides a data-generation tool that allows you to analyze and measure," Allen says. It provides "visibility and knowing where your hiccups might be," enabling you to then take action and make improvements.

RFID tags are also made to be durable, which can be an advantage over paper bar codes which, if scratched, bent or wet, can become unreadable, he says.

Allen is seeing an increase in the use of RFID along the food chain because of its advantages, retailer mandates and decreasing expense. And many of those who began its use in order to be in compliance with a retailer, he says, "have rolled back the use of RFID further and further into the supply chain." An example Allen gave of this is the Ballantine Produce Company. Their first step was to become compliant, but now, he says, "they envision getting value out of that, to even go so far as to analyze and track soil production."

RFID is relevant to both small and large plants, but a plant shouldn’t jump into a system without due consideration. "RFID is a very powerful, enabling tool when it is implemented intelligently," Allen says. "Outside of a mandate, it’s incumbent upon them to find value in the use of RFID. We encourage folks to educate themselves on the technology – it’s not a ‘plug ’n play’ technology." Prior to deciding to implement RFID, a plant should:

• educate itself on the technology

• set expectations of what it wants to

accomplish

• determine where it would be most useful

Then, if the plant believes it has potential for RFID, Allen says, "start small." Put a system in place; if the plant gains efficiency improvements, roll the system out further. "Continue to analyze the data. If indeed it is helping, roll it out to the entire enterprise," he says. "Being able to collect data, analyze data, measure it and prove the ROI – that is the ultimate test."

"There may be only one segment in your supply chain that will benefit," Allen adds. But if you can justify it even at a single point, such as pick packing, go ahead and implement it there.

RFID does have negative aspects as well – there can be issues with reflection on metallic surfaces and it does get absorbed by liquid. "These things do have to come into play as you analyze and test your process," Allen says. It’s not necessarily that it won’t then work, he explains, it just may reduce the read range. And like any wireless technology, "it has obvious benefits, but there are also obvious costs that go along with it." But, again like much of technology today, costs have decreased, and Allen says, "we will see a continued evolution of cost downward." At the same time, the capability of the systems is continuing to evolve upward, he says. "It’s still a young and burgeoning technology."

TEMPERATURE TRACKING. Our increasingly global economy is adding to the drive for tracking and traceability. Not only with the increased defense guidelines to combat bioterrorism, but also because of increasingly rigid export mandates, which appear to be impacting U.S. manufacturers and suppliers.

One example of this is the need for temperature tracking. Maryland-based AmeriScan Inc. is a part of the Euroscan Group, headquartered in Bonn, Germany. Many of the European nations require that suppliers be able to produce records of temperature points at loading, unloading and in between, says President and Managing Director Christoph Kalinski. "Everyone in the supply chain needs to produce the temperature readings within 24 hours." This means you need to have these readings easily accessible in a central location so they can be quickly retrieved. In addition, the supplier and/or transporter can be held personally liable if the temperatures cannot be proven, Kalinski says.

Kalinski does see these European regulations as impacting U.S. guidelines, with the expectation that action will begin on the West Coast, in California, which generally upholds stricter requirements than national standards. "We’ve talked to lots of people in California who say these are definitely coming here within the next two years," Kalinski says. In the Midwest and East, though, suppliers are more likely to say, "That will never happen here."

There is also a movement toward temperature monitoring and control because of the amount of food waste attributable to inadequate temperatures. "We expect it to become a stricter requirement in California since they have a substantial problem with food poisoning and food waste," Kalinski says, adding, "Usually it’s due to temperature, but not exclusively." An average of 25 percent of all food goes to waste because of temperature, incorrect loading or shelf life issues. "That’s why there’s such a movement going on now."

People are also becoming more aware and realizing the issues that arise from temperature variances, but, more importantly, technological advances have enabled suppliers to track and prove temperature variance and related issues. Before this technology, Kalinski says, "Everyone knew it, but no one had proof of it."

But the new technologies don’t only track and monitor the temperatures, they control them. Though still a fairly new concept in the States, AmeriScan’s temperature-recording system, for example, has been in use in Europe (through EuroScan) since 1994. Such systems combine hardware equipment with a communications interface, providing complete information along the chain — tracking not only temperature but also door openings, humidity, CO2 and oxygen levels, and transportation speed; and making this information available in real-time via the Internet. "It provides complete control over what’s happening with your assets," Kalinski says. "The food processor can make sure that their product is delivered to the quality standards that they are requiring. You know what the temperature is and that your quality is guaranteed."

The automated systems also provide efficiencies and fixed controls over hand-held, manual data loggers and enable fulfillment of HACCP guidelines, with monitoring and assessment of the critical control points that occur each time a product changes hands. "It guarantees correct temperature readings at the point of delivery and point of loading, and guarantees that the producer is in control of the process that is required by HACCP," Kalinski says, adding, "It is extremely difficult and very arbitrary if this critical control point is put in the hands of suppliers or workers." In fact, the company is communicating with USDA and FDA on the potential of conducting a pilot study to demonstrate how such systems can increase the agency’s ability to enforce regulations.

INCIDENT ALERTS. In addition to the technological developments of systems that directly track or trace foods and packages along the chain, technologies have sprung up that provide associated benefits to a processor’s systems. Such systems provide an essential add-on supplement to a plant’s traceability system. As USDA notes in the publication, "Tracking food by lot in the production process does not improve safety unless the tracking system is linked to an effective safety control system." Traceability systems do not create product safety and credibility; they simply "verify their existence."

One such add-on is the surveillance and incident alert system, a service that provides "an adjunct and empowerment tool for traceability systems," says Robert Waite, president of FoodTrack Inc., Palm Beach, Fla.

Food companies utilize traceability systems for a multitude of reasons, Waite says, including quality standards, bioterrorism-regulation record keeping, customer-requirements and recall needs. "You need to be able to trace it back, so across the board, everyone will be better equipped to respond." An alert system does not trace the product, but provides an adjunct to a company’s tracking system and comes into play when there is an incident.

When an incident or outbreak occurs, it is not always immediately evident as to the extent of contamination, where along the chain the problem occurred, which ingredient was tainted, or where that ingredient originated. But the sooner a plant is aware of an incident, the sooner it can take action in checking its own supply lines and stopping the distribution of an affected product or even holding a suspect ingredient to keep from potentially producing a contaminated product.

An example Waite provided was a recent cocoa contamination. In early April an organic chocolate product was recalled. It was determined that the tainted ingredient was raw cocoa from Ecuador. Because this area is a major supplier of cocoa, there was potential impact to numerous chocolate product producers. FoodTrack issued an instantaneous alert, enabling producers to review their traceability systems, seeking any product sourced in Ecuador. The plant could then contact its buyer to track whether the plant had received any of the tainted product, or if there was even a chance that the product purchased could be tainted.

The proactive alert system is particularly critical on weekends and holidays, Waite says. Incidents that occur on Friday evenings can have the most potential for outbreak, as the weekend is a major shopping time, but plant managers are often out of their offices until Monday morning, giving the entire weekend for the event to escalate. With a real-time alert system, the manager or designee is notified electronically or by pager of related incidents, so they can react immediately.

With standard traceability, plants are notified if a supplier is involved in a recall, but this is pending trace back to determine the source, which can potentially take a week or two even through federal agency systems, giving that much more time for a tainted ingredient to get into products. "What good is the best traceability system if you’re not notified; if you don’t become aware of an event that you might have to trace back through your system?" Waite asks.

Proactive alerts, he explains, "put you in a position to prevent tainted ingredients to be used in your product and distributed to the retail market. That’s one way a company can sidestep an entire event." The system can also be helpful even when the producer conducts a trace-back and finds all products to be clean. Producers are often bombarded by inquiries when a recall occurs, with retailers and consumers asking if their product is affected, and regulatory officials tracing the source of contamination. Rather than answering, "I don’t know," the producer can affirm that its product is safe, stating, "We already checked with our suppliers; here are the records."

The key advantage of a proactive incident alert system is that companies know about recalls and contamination events sooner and can proactively address them, Waite says. "Everyone is notified eventually. The whole point is when you are notified, not if. It only makes sense to have the information as early as possible even if it buys you a five-minute phone call to assess your liability."

TECHNOLOGY COST BENEFITS. The continuous evolution of technology is providing processing plants with new and continually improving methods of tracking and tracing their products both forward and back – and, even better, the technological advances mean that many of these systems are becoming more and more available at ever-decreasing prices. The key to the decision on whether a plant should implement a new technology comes down to individual value in connection not only with a company’s general budget but also maintaining its product quality and brand equity.

Even USDA recognizes this, noting in the publication’s description of food safety and quality control benefits, "Traceability systems help firms minimize the production and distribution of unsafe or poor-quality products, which in turn minimizes the potential for negative publicity, liability and recalls."

While government agencies have considered mandatory traceability and have implemented some regulations along these lines, "the already widespread voluntary use of traceability complicates the application of a centralized system," the publication says. "Mandatory systems that fail to allow for variation are likely to impose unnecessary costs on firms that are already operating efficient traceability systems."

Follow the same test for any technology-related decision as Allen described for the RFID: Educate yourself, set goals, determine its usefulness, run a pilot, analyze the results and measure its value. No single system is right for everyone, but technology is making it easier to implement the tracking and traceability systems that are right for you. QA

Explore the Summer 2006 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- FDA Releases Produce Regulatory Program Standards

- Invest in People or Risk the System: Darin Detwiler and Catalyst Food Leaders on Building Real Food Safety Culture

- USDA Proposes Increasing Poultry, Pork Line Speeds

- FDA Releases New Traceability Rule Guidance

- TraceGains and iFoodDS Extend Strategic Alliance

- bioMérieux Launches New Platform for Spoiler Risk Management

- SafetyChain Receives SOC 2 Type 2 Certification

- Puratos Acquires Pennsylvania-Based Vör Foods